Part I. The Problem With Religious Experience

By Stephen Busic

Alter calls were interesting where I grew up. Especially in youth events. The chapel lights would dim and the speaker’s voice would lower. A synth pad softly soundtracked his words. Whatever chords guided the last worship song we sang, that’s what the pianist looped. The rest of the band prayerfully held up their hands. Something like “If you feel the spirit moving, come to the front!” would leave the pulpit. This is a very stereotypical picture for a lot of us raised under western, protestant Christianity. It’s the first thing I think of when I hear the phrase “religious experience.” And many of us highschoolers felt some sort of experience at these events. I remember tearing up and sensing what I took to be God’s presence. Looking back, I can point out the intoxicating effects of stage lights, fog machines, social pressure, and music. Not to mention my strong and perhaps self-fulfilling desire to “feel something.” These things are sufficient to generate the feelings I felt, I think - no divine intervention needed. But to stop wondering about religious experiences and reject them here, as many skeptics like myself sadly do, is hasty and unfair.

For one, many Christians have religious experiences in settings far less performative and flashy. They sense God while alone, idle in places of no particular importance, in no special scenery, set to no soundtrack. Secondly, faith traditions from countless eras and cultures report their own religious experiences. This is not a phenomenon limited to, let alone best represented by, modern American mega churches. Mystical experiences, whatever you think they are, are described across the world’s ancient writings as well as today, and found in settings highly diverse. These facts show that religious experiences are often had outside emotionally loaded or engineered settings like my high school youth events. Thus, it’s harder to write them off as being caused by purely natural phenomena. If skeptics want to somehow discount religious experiences, it'll take a stronger argument, and preferably one that works on the believer’s own terms.

So here we are! I think there is such an argument. I rewrote this article twice and drowned in a lot of published religious philosophy. I’m still worried I won’t do it justice. Religious experiences are a worthy phenomenon for skeptics and believers alike to consider. If you’re ready for a rewarding rabbit hole on these experiences, and what if anything they can tell us about the world, I’ll be honored to take you with me throughout this post. I should quickly say that by “experience” I just mean a conscious event – the total of every inner feeling and sensory input that makes up someone’s awareness at a given moment. I am not using the word to mean the wisdom gained by time-worn people, as in the phrase “life experience”. I am only taking the word to mean a conscious moment in our mental lives. (Although, some people do take “life experience” such as personal guidance and growth to be evidence that their particular religion is true. A challenge here is that many different religions positively affect the lives of their followers, not just one. I’ll write an article about this too, if requested!) But in this post, we are only going to evaluate the latter kind of inference – that mystical experiences can serve as evidence for one’s faith.

I’ll go ahead and reveal my hand. I don’t think they can. I’m not calling anyone mistaken about what they felt, or worse a liar. Under my skeptical argument, it’s possible that many religious experiences are in fact of God. Even still, I don’t think one can use them as evidence for God’s existence, nature, or actions. That might sound strange to you. Once I defend it, maybe it’ll make more sense. Just know that my skeptical take alone won’t threaten the authenticity of anyone’s experiences, let alone the truth of anyone’s religion. If I’m right about this, it will only show that these experiences are not a reason to think any religious or spiritual claims are true. Other reasons to believe such claims could still be out there in plenty. Now for the record, I do identify as an atheist. But since my argument works on terms a believer already accepts, my nonreligious views are irrelevant in this post. Many religious thinkers share the skeptical view I will argue for here, and all of the philosophers I cite and rally with in this post happen to be theists. So, those disclaimers out the way, let’s get begin our deep dive. Before we can get into the (plant-based) meat of this article (read my strong case for veganism here ;)), we will have to carefully wonder two things: 1) under what conditions can or can’t our experiences tell us anything about reality, and 2) does the answer to this question challenge the mystical encounters on which many people justify their faith?

Religious Experiences Defined

For our sanity, we’ll have to define some stuff. First, every experience has at least a subject and an object. The subject of an experience is the individual having that experience; they are the audience to that conscious event. The object of an experience is what’s on stage; it is the stuff the experience is of. If I told you about an experience I had of Yosemite National Park, I would be the subject of that experience, and the object would be Yosemite. Of course, at any moment of our daily experience, there is rarely just one object at play. Consider your morning. In a single second of your morning experience, there may have been the quiet hum of a fan, the warmth of a mug, a lingering yawn, and so on. Hundreds of things both internal and external to you are at all times forming an orchestra – a diverse ensemble responsible for all the ways that right now feels. Some of these objects will win your attention more than others. But all together, there is usually a lot streaming on and off your conscious stage.

This concept of subjects and objects is needed for us to define what a religious experience actually is. In short, an experience is religious insofar as one of the objects of that experience is divine or spiritual. Experiences can be more or less religious under this definition. They can also involve non-religious “natural” forces, just as long as those forces are not the only ones at play. Believers may have religious experiences of all kinds and intensities – a blinding light on Damascus Road, or just a subtle feeling God is present. Experiences anywhere on this spectrum give people emotional fulfilment, a sense of guidance or self-insight, and motivation, among other things. Most relevantly to our discussion, they are also said to provide knowledge of the divine. That is, people who undergo them can learn something about what the divine is like. Let’s call this the “revelatory view” of religious experience. According to the revelatory view, religious experiences can reveal to us (and hence support claims about) the divine’s existence and nature. Many theists would say their knowledge of God has come partially, maybe even mostly, by religious experience. And hence, they agree with the revelatory view.

It’s not just theists making claims like this, either. In fact, the words “divine” and “spiritual” might already assume too much. Nontheistic religions such as Buddhism and Jainism do not believe their mystical experiences are of a personal creator god, of spirits, or of any conscious being at all. To account for nontheistic religions like these, we will need language that is more general. A catchall phrase sometimes used in philosophy of religion is the Ultimate Reality, or the Ultimate for short. Webster’s dictionary, not shy of the challenge, offers a definition of the Ultimate. They put it as “something that is the supreme, final, and fundamental power in all reality.”1

An obvious and driving question in philosophy of religion, then, is What/Who is this Ultimate Reality? Of the many candidates humans have put forward, It has been an “individual, a state of affairs, a fact, or even an absence, depending on the religious tradition the experience is a part of.”2 So to be theologically inclusive, I will continue to use the broader term “religious/mystical experience” instead of “spiritual/divine experience.” Religious experiences to us will not mean just any experience had in the context of religion. Rather, this phrase will only reference those experiences that are of the Ultimate Reality, to whatever degree. These are a lot of clarifications I’m making, I know. Don’t let them fool you. The fact of religious diversity is far from just a definitional inconvenience. Later on, it will mark this article’s most heated philosophical warzone.

Sense vs. Religious Experiences

Let me repeat my thesis. I think no religious experiences even if real and genuine can teach us about the Ultimate Reality. In other words, I think the revelatory view is false. Again, I’m not doubting the legitimacy of anyone’s mystical experiences. I only hold that these encounters, despite feeling exactly how many honest people say they do, should not be trusted as revealing anything about the Ultimate. As said, this is far from saying God(s) does not exist or any religion is false. I am only arguing that if God(s) exists, religious experiences are not a way we could know about Them.

What might surprise you is that, even with this skeptical view, it has never struck me as obvious that people shouldn’t trust their mystical experiences. After all, these are experiences. Unless we have reason to doubt our experiences, most of us take them to be reporting something true of the world. Take the experience afforded by our senses, like sight, sound, or touch. If you’re a sighted person and you walk outside and see a tree, you can safely believe that tree exists. It is possible you are wrong, of course. You might be hallucinating or seeing a very convincing cardboard cutout. But absent any reason to think your eyes are tricking you, you are entitled to trust them. Sense perceptions are innocent until shown guilty. That’s how a lot of us treat them, anyway. And if that’s right, then it’s hard to see why sense experiences can enjoy that privilege, while religious experiences cannot. Granted, it may be a bit harder to pin down by what faculties people have the latter. Some religious experiences are said to involve the physical senses, but most who have them describe an internal sort of perception – a “spiritual analog of the eye or ear.”2 Nonetheless, these experiences appear to many people just as vividly as sense perception ones. Why shouldn’t we give them the same initial trust?

Phenomenal Conservatism

What you just heard was an argument from consistency. It pushed the claim that it would be arbitrary to trust some perceptions by default – like the ones afforded to us via bodily senses – but not others, such as those of a more spiritual sort. Of course, a skeptic could grant this argument and just withhold trust for all perception equally, sense or religious. But this would be a very radical move. I’m going to assume you think your sense experiences can tell you about the existence and nature of the world. Otherwise, you’re likely doubting if the words you’re reading might now are even mine and from a real article, rather than a hallucination. Don’t get me wrong. The question of whether we can trust any of our perceptions is a profound and reasonable one. It’s not a silly thing to ask. But most of us already think our senses can tell us about the world, so any defense of that would be better housed in another article. For now, we will just “assume that things are the way they seem, unless and until one has reasons for doubting this.”3 I use quotations because this happens to be the very definition of a view called Phenomenal Conservativism. We won’t be using that clunky term much. Just think of this view as the “innocent until reason for guilt” view for our perceptions. If there is no reason to distrust your experiences, you are entitled to trust them without any independent evidence.

The Experience Argument for Religious Belief

The familiar line said by skeptics like myself is that absent a sufficient amount evidence, theism is unjustified. But we don’t seem to have that attitude toward trees! Can the existence of God can be treated much like the existence of the material world – justifiably assumed on the basis of experience even without independent evidence (unless and until one has reasons for doubt)? Theistic philosophers such as William Alston and Alvin Plantinga have famously argued yes – religious belief can be justified on the basic of mystical experiences alone. If Alston and Plantinga are right about this, then any independent arguments for theism would just be icing on the cake – extra justification for something that can already be safely believed based on mystical perception. If it can be experienced, it can be trusted, at least initially. And who could deny the fact that many say they experience God? It is by this argument that Plantinga defends the following stance, which is a common thesis in Reformed Theology:

“…belief in God need not be based on argument or evidence from other propositions at all. […] [T]he believer is entirely within his intellectual rights in believing as he does even if he doesn't know of any good theistic argument (deductive or inductive), even if he doesn't believe that there is any such argument, and even if in fact no such argument exists.”4

If this sounds dogmatic to you, Plantinga would ask you to replace “belief in God” with “belief in trees” and read it again. However hardcore of an atheist you may be, don’t you think it’s within everyone’s intellectual rights to trust their experiences of trees? Even if they don’t know any good arguments? For theists, this argument is obviously a jackpot. If successful, it would defend religion in way that is not only strong, but fiercely accessible. It isn’t just the religious philosophers who, after slaved away at the arguments for years, could enjoy a rationally justified faith. It’s the average believer. Plantinga’s argument would publicize religious justification and give it the same strong footing as our belief in the external world. It’s hard to find a better deal than that.

The Challenge of Religious Diversity

So, what’s the issue then? Why don’t I and others buy it? I mean, I do agree that we can take our experiences, religious and sense alike, be to true absent any reason for doubt. That’s the mantra of Phenomenal Conservatism, an intuitive enough view which I personally hold. And yet, I don’t think religious experiences can tell us anything about the existence of God. Why is that? It’s not because I withhold trust in all experiences equally. I enjoy a healthy belief in trees like you do. Rather, I am not swayed by religious experience because I think there are serious reasons for doubt. And these fatal reasons are not present in the experiences from our bodily senses.

The trouble begins when we appreciate the sheer diversity of religious experience. Within a single faith tradition, there can be a dozen ways that followers take themselves to be experiencing the Ultimate Reality. Around 4300 notable religions are being practiced today around the world.5 It is hard to say how many religious have lived in died throughout the roughly 50,000 year-long human story, but the total number is certainly greater. Moreover, it’s plausible that of the estimated 11 other hominid species that either preceeded or once lived alongside us,6 some of them (particularly Neanderthals) may have had religiosity of some kind.7 Point is, there has been many, many sorts of religious experience. This prevalence might first seem to the benefit of religion. But one problem quickly converts it into a challenge. The problem is that all of these many religious experiences often contradict.

Religious experiences play by the same rules as sense perception ones. That’s what Plantinga showed us with his argument. However, this might be dangerous for believers argue. You cannot take the epistemic strengths of sense experience without its weaknesses! And one trouble for sense experience is that when multiple observers have contradicting reports about something, we can only rationally withhold belief about what was seen. No information can be revealed by the experiences. As Mark Webb puts it:2

Religious diversity is a prima facie defeater for the veridicality of religious experiences in the same way that wildly conflicting eyewitness reports undermine each other. If the reports are at all similar, then it may be reasonable to conclude that there is some truth to the testimony, at least in broad outline. […] But if two eyewitness reports disagree on the most basic facts about what happened, then it seems that neither gives you good grounds for any beliefs about what happened. It certainly seems that the contents of religious-experience reports are radically different from one another. Some subjects of religious experiences report experience of nothingness as the ultimate reality, some a vast impersonal consciousness in which we all participate, some an infinitely perfect, personal creator.

Philosopher John Hick calls this argument “an obvious challenge” and “a reversal of the principle, for which Alston has argued so persuasively, that religious experience constitutes as legitimate a ground for belief-formation as does sense experience.” He goes on to say that “the same epistemological principle establishes the rationality of Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, etc. in holding beliefs that are at least partly, and sometimes quite radically, incompatible with the Christian belief system.”8 (25-26) Notice this problem doesn’t exist with trees. There is virtually no widespread disagreement about the basic facts of trees, or the physical world in general. If any two sighted people are looking at a brick, it’s unlikely their descriptions of it would differ much, let alone contradict. Yet, if any two religious people describe the Ultimate Reality, the details will likely be very different and conflicting. There is almost no widespread agreement about the object(s) of religious experiences, and this calls into question how much we can believe from those experiences. Call this the “Objection from Religious Diversity,” or ORD for short.

Explaining the ORD

The ORD is a serious epistemological challenge for anyone who takes religious experience to be informative. If you think religious experiences can tell us anything about the Ultimate Reality, you’re going to have to resolve this objection. There is no way for both the ORD and the revelatory view to coexist without causing a contradiction. Alright. Now that I’ve made this objection out to be big and scary, let’s see it as a deductive argument.

Premise 1: When there are many real yet conflicting experiences of something, none of them can be justifiably taken to reveal anything about the nature of that thing.

Premise 2: There are many real yet conflicting religious experiences of the Ultimate Reality.

Conclusion: Thus, no religious experience can be justifiably taken to reveal anything about the nature of the Ultimate Reality.

The first premise is a difficult one to deny. If all the conflicting reports are just as real and honest, they are all just as worthy of trust. We wouldn’t be very rational if we arbitrarily picked one report out of many equally legitimate reports and called it true. But because they conflict, we also can’t trust all of them. That would have us holding contradictions. So, in such a case, we must trust none of the reports. Withholding belief might not be what we want. But when the only other options are to unfairly favor some of the reports and not others, or believe in contradictions, withholding belief doesn’t sound so bad.

Premise 1 is secure, then. If there is a weak point in this argument, it’s going to be with premise 2. Notice the two words real and conflicting in this premise. We need both adjectives to be true of religious experiences for the ORD to work. A discussion of what we should mean by “conflicting” will come later (warning: it’s complicated!). For now, let’s just say two experiences conflict only if they claim to be of the same thing, and yet yield descriptions that contradict each other. Meanwhile, by “real”, I just mean that the experience really is of the Ultimate reality. Many believers think that someone could have an experience which seems like it’s of the Ultimate, but really isn’t. The cause of this false religious experience might be a placebo effect, social pressure, drugs or hallucinations, or anything other influence seen as misleading. Since I defined religious experience as being of the Ultimately Reality, a false religious experience is really no religious experience at all. It's just a deceptive lookalike. Yet, I will keep using “false religious experiences” to refer to these lookalikes, and “real religious experiences” to refer (albeit redundantly) to those experiences that really are of the Ultimate Reality.

Two Ways Out – A Dilemma

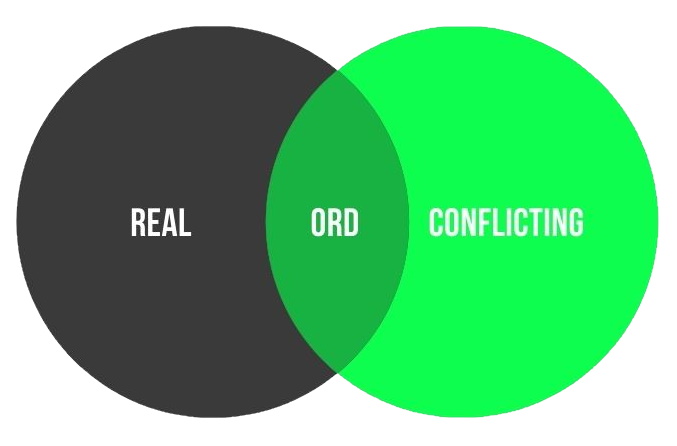

I said that we need both adjectives – real and conflicting – to be true of religious experiences for the ORD to arise. As a math major, I try to shove graphs into any conversation. So, here’s a Venn diagram.

Any overlap between these two circles, and the ORD will rear its ugly head. That means there are two broad ways to prevent overlap and save the revelatory view. First, you can argue that only one non-conflicting set of religious experiences is real. For example, a Christian might say that while it’s true religious experiences conflict across religions, only Christian religious experiences are real. And since real Christian religious experiences do not contradict each other, so the argument goes, there are no two religious experiences that are both real and contradictory. No overlap remains, ORD adverted. Call this the “exclusivist” solution. Alternatively, we have the “universalist” solution. (Not to be confused with the Universalist view on salvation – very different!) If upon closer look, there just are no contradictions among the diverse spread of religious experience, then that would remove the conflict too. This amounts to shrinking the “conflicting” circle to be very small if not non-existent, which would avoid overlap. Defenders of this view will often explain away contradictions by locating them in the human-contributions we make when having a religious experience (and hence outside the Ultimate Reality’s contribution), or take the contradictions to be true descriptions of differing parts of the Ultimate Reality, rather than mutually exclusive descriptions of the whole.

Once the overlap is avoided– either by the exclusionist or the universalist strategy – then we could have a situation much like we do with trees. Everyone’s real experiences of the same tree wouldn’t differ much, let alone contradict. So, absent conflict and any other reason for doubt, we can justifiably take trees to be as they seem, no further arguments needed. That’s also Alston’s and Plantinga’s hope for mystical experience. But to achieve it, one must vanquish the objection from religious diversity. These two strategies – the exclusivist and the universalist – are the only solutions to the ORD, which in turns makes them the only alternatives to the skeptical view. To better remember each one, here is way to capture the heart of both solutions. Regarding religious experience, exclusionists say that realness is less common than it seems, while universalists say that conflict is less common than it seems. That about says it.

See how I snuck the word “seems” in each? Both camps will be fighting against intuition. It seems true that real religious experiences happen under all faiths, and that these experiences lead to theological conflict. As Hick puts it, “Belief in the reality of Allah, Vishnu, Shiva, and of the non-personal Brahman, Dharmakaya, Tao, seem to be as experientially well based as belief in the reality of the Holy Trinity,” and that between these faith traditions, “incompatibility is clearly very considerable: God cannot be, for example, both personal and not personal, triune and not-triune, primarily self-revealed to the Jews, and to the Arabs, and so on. And yet religious experiences within the different traditions has produced these incompatible beliefs.”8 (25-27) Embracing both of these appearances and accepting overlap is exactly what the skeptical view amounts to. For the rest of this post, I will attempt to show why I think the exclusive and universal solutions fail, leaving the skeptical one as the only choice.

One last thing: not every theological conflict between faith traditions is being considered in our discussion. Only those conflicting theological claims that are based in religious experience are relevant. Christianity and Hinduism, on some interpretations, disagree wildly on the age of the earth, for example. But the earth’s age as a theological teaching is likely not directly mystically experienced by believers in either religion. Contradictions between religious can fuel the ORD, notes Alston, “only if mystical perception-based beliefs figure prominently in a significant number of those incompatibilities.”8 (44) If the conflicting religious beliefs aren’t backed by religious experience, they aren’t relevant to us. To what extent theological contradictions are thus backed is another way to frame this entire debate.

Solution One: Exclusivism

You might be wondering which route Plantinga takes. It’s this one! He favors a humble yet blunt exclusivism. He writes that “with respect to religion positions incompatible with my own […] I believe (sometimes in fear and trembling) that they are not as well based, epistemically speaking, as my beliefs.”8 (54-56) Exclusivism solves the ORD by limiting the number of real religious experiences to a noncontradictory few. Any religious experience outside of this few is explained away as being false – not really of the Ultimate Reality. The challenge for exclusivists, though, is to explain how we can tell real and false religious experiences apart. Absent a method to separate the real from the lookalikes, exclusivists will have no way to justify their central claim – that only one nonconflicting set of religious experiences is real, and the rest are counterfeits. The success of their view is dependent on some mark of authenticity being common to all real religious experiences, and absent in every false one.

It’s not that without such a marker, the exclusivist must then be mistaken. It’s just that without a marker, the exclusivist has no way to know she’s right even if she actually is. Suppose you are handed a real dollar bill, while 99 other people in the same room are handed perfect counterfeits. How could you verify that you are the lucky winner? Absent a marker, nothing could tell your dollar is real. It is indistinguishable from the lookalikes. However authentic your dollar feels to you is exactly how the other 99 feel about theirs. In such a scenario, there is no way you could tell if you were handed the real one. And so, it would be unjustified to think you were. What’s interesting is this would be the case even if you are in fact the one with the real dollar. Clarifying this point is a bit unnecessary, though. Whether the absence of a marker falsifies or just removes justification from exclusivism makes no practical difference. We would reject it either way. Bottom line is that exclusivists need a marker!

Feel and Virtue as Markers

Now, there is an unfortunate way some exclusivists will go about this. They’ll say the marker is some fact about how the religious experience feels – or worse, how it “bears fruit.” A Christian exclusivist, for example, might say Christian religious experiences just feel more potent or sincere in some way than those of other religions, or that Christians are stirred to lead more virtuous lives by their experiences than are Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and so on, and that’s the mark of authenticity. Aside from arrogant or xenophobic, this claim that one religion has a monopoly on religious experiences of a certain caliber and moral uplift is just false. Many followers of Islam, Buddhism, Taoism, etc. have mystical encounters just as sincere as followers of Christianity. They report their experiences to be authentic and compelling. They feel no fewer stirrings during worship or mediation. They also lead virtuous lives, and credit much of their moral wisdom to their faith. Denying these things is just factually wrong, if not conceited. We would all be in our right minds to agree with Hick when he says “each of the great faiths, theistic and non-theistic, is […] supported by religious experience, supposed revelation, revered scriptures, inspiring role models and a more general uplifting effect in people’s lives,” and that “the good effects of religious faith in many people’s lives are also not confined to any one tradition.”8 (41)

Doctrinal Agreement as a Marker

So, we will take it that experiences under many religions can all feel just as convincing and powerful. They can also all be just as morally inspiring. With these possible markers out, what candidates are left for a sign of authenticity? Maybe the most popular suggestion is doctrine. Exclusivists often say that the mark of a real religious experience is that it aligns with teachings of the one true religion. I’ve often heard Christians say that religious experiences are real so long as they don’t contradict the Bible. This is a more reasonable proposal. Yet, there are some things to say about it.

First, anyone holding this view better not base their faith on religious experience. Why? Because they only trust religious experience if it matches the teachings of their faith. This is a textbook case of circular reasoning. They would have to say, “I know my religious experiences are true because of the Bible, and I know the Bible is true because of my religious experiences.” Clearly, if the only way to verify real religious experiences is supported by religious experience, then we have a vicious circle on our hands. It would be like sending instructions on how to verify the authenticity of a letter by mail. What these exclusivists need is to establish the truth of their religious doctrines on grounds wholly independent from religious experience.

For exclusivists like Plantinga, this would take a full-fledged case for Christianity without appealing to religious experience at any stage of the defense. A completely non-experiential defense of religion could be very hard to make. Hick points out that “Many of us today who work in the philosophy of religion are in broad agreement with William Alston that the most viable defense of religious belief has to be a defense of the rationality of basing beliefs (with many qualified provisos which Alston has carefully set forth) on religious experience.”8 (25) Lots of religious philosophers think that arguing from mystical experience is the best shot at justifying religious belief. Without that option, making a full defense of any particular religion could be far more challenging. I personally do not think it has been done.

But if a complete non-experiential case is successfully made, then fair enough – I’ll grant that they would then have a method to tell the false religious experiences from the real ones. With such a method in hand, the verified “real” religious experiences would not conflict (all being consistent with the same doctrine), and so could serve as evidence for claims about the Ultimate Reality. The revelatory view is saved! However, it is saved at a point far beyond when Christian philosophers could have made good use of it. All the hard work of establishing Christianity would have already been completed. What’s left for religious experience to support? It could only sprinkle on extra unneeded evidence of Christianity’s essential claims, or support nonessential claims which, however theologically interesting or personally meaningful, are still nonessential to justify Christian belief. Religious experience is removed from the toolbox of Christian apologetics. Whatever purposes are left for it to serve, they come along after the rational defense of mere Christianity is complete.

In such an outcome, the goal Plantinga and Alston have for religious experiences is lost. They wanted to use religious experience as a grounding justification for religious belief. They hoped belief in the Christian God could be defended in the same easy way we defend belief in trees, no further arguments needed. But this dream is the casualty of the exclusivism. While the existence of trees can be justifiably and happily accepted based on experience alone, believing in the existence of God is going to take some arguments. And insofar as the average believer lacks those arguments, that believer is unjustified in their religious belief.

Solution Two: Universalism

So, the exclusivist can save the revelatory view, but only with a complete non-experiential defense readily on hand for a particular religion. That’s a hefty prerequisite. How promising is the universalist strategy, and can it avoid some of exclusivism’s challenges? Turns out this is no small or boring question. It threw me into such a rabbit hole that to do it justice, I had to split this article into two parts! See how our investigation into religious experience concludes here!

1 “Ultimate reality.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ultimate%20reality. Accessed 4 Oct. 2021.

2 Webb, Mark. “Religious Experience.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford University, 13 Dec. 2017, plato.stanford.edu/entries/religious-experience/.

3 Huemer, Michael (2013). Phenomenal Conservatism. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

4 Plantinga, Alvin. “Is Belief in God Properly Basic?” Noûs, vol. 15, no. 1, 1981, p. 41., doi:10.2307/2215239.

5 Adherents.com: Religion Statistics Geography, Church Statistics. United States, 2002. Web Archive. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/lcwaN0003960/>.

6 Wood, Bernard, and Brian G. RIichmond. “Human Evolution: Taxonomy and Paleobiology.” Journal of Anatomy, vol. 197, no. 1, 2000, pp. 19–60., doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x.

7 King, Barbara J.. Evolving God: A Provocative View on the Origins of Religion, Expanded Edition. United Kingdom, University of Chicago Press, 2017.

8 Hick, John. Dialogues in the Philosophy of Religion. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Login to comment!

Use an existing Google, Twitter, or Facebook account to comment on posts. Quick and easy!

No comments yet... be the first!